One objective of this website is to help people to separate facts from illusion. This and its sister websites contain more than 50 cases involving such illusion.

Facts are important because we make many decisions based on facts, some of the decisions can be life changing. For example, we want to live in a low crime area. The number and types of crimes in an area is a fact. They provide important input to our selection of a desirable area. If we are wrong in the facts, we may make the wrong decision on where to live. This is an important decision because it can affect where we raise our children, establish a career or business, retire, etc.

What is fact? What is knowledge? What is belief? These are metaphysical questions pondered by philosophers for thousands of years. We don’t know the answer. Instead, We will look at it at a practical level. Let us provide a definition of “fact,” which others may not agree. Nonetheless, establishing a clear definition is an important starting point of inquiry.

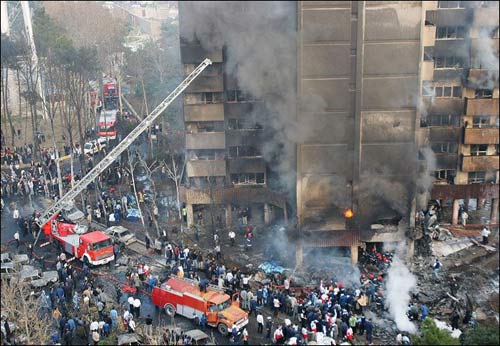

Envision a big fire at a multi-storey building located in a big city. There are residents in the building trying to escape the fire. Fire-trucks with firefighters and ambulances with medics arrive on the scene. There are curious bystanders wanting to see what is going on. Because big fires are generally newsworthy, reporters also show up. They later broadcast videos or print the news so people in the city know about the big fire.

Imagine a science fiction extension to the situation: there is a battery of fire-resistant drones flying everywhere in the building and outside. The drones are armed with smoke-penetrating high definition cameras and “write-once-read-many” memory (Wikipedia defines it as “a data storage device in which information, once written, cannot be modified.”). The cameras and memory are working all the time to record the fire. We consider the recording of all the drones stored in the write-once-read-many memory as “facts” associated with the fire. It is relatively comprehensive (lots of drones flying everywhere), unbiased (everything is recorded instead of selective recording), unemotional (images are not filtered) and unalterable (to prevent revisionist history).

Soon after the fire started, many people know the existence of the fire. They are:

(1) People who have direct interaction with the fire. They include building residents, firefighters and medics.

(2) People who directly witness the fire. They include bystanders and reporters.

(3) People who watch or read about the fire through TVs and/or newspapers. They include people of the city who were not at the scene. The vast majority of people belong to this group.

Question: How do all these people perceive the fire at the time of the event, or, for people in group (3), at the time of watching/reading reporting of the event? How do people remember the fire days, months, and years after the event? How accurate is their perception and memory of the fire?

Note that We are interested only in people’s perception and memory of the fire compared to the “facts”, which we define as recording in the write-once-read-many memory. We are not interested in opinions such as whether the firefighters and medics did a good/poor job, or whether the design of the building hindered/helped the residents’ escape, or whether the city has sufficient/inadequate number of fire stations so firefighters can reach the fire site quickly, etc.

People form opinions based on their perception of the “facts.” When the time comes for residents to vote on whether or not to hire more firefighters, build more fire stations, and change building code, the “facts” they believe in can affect their votes.

Unsurprisingly, there are vested interests who want to alter our perception of "facts." Just a few examples from the big fire: real estate developers want to minimize the impact of the fire to avoid strict building code that can hinder their ability to build tall buildings, fire department wants to emphasize the damage caused by the fire to get a bigger budget to run the department, city officials want to to ignore the fire so they can portray the city in the best light to attract outside investment to the city, etc.

How can we prevent these vested interests from altering our perception of "facts"? Unfortunately, we don't have the science fiction drones at our disposal so we can do a fact-check using the write-once-read-many memory. A starting point to fight with the vested interests is to learn the deceptive tricks used by them.

On this website, we discuss a large number of cases of real events and real persons, including those who lost big money to swindlers, rendered homeless in a foreign country, and even lost their lives -- all of them were misled to develop certain perception of facts that turned out to be illusion.

Let us get into more details about "facts."

Most people think that the facts they perceived and believe in are correct. They use the "facts" stored in their brains to make decisions.

Questions:

(1) How do people acquire the “facts” they believe in? In reality, many information we believe in turn out to be false at the time of acquisition.

(2) What happen to the “facts” in our mind after acquisition? Let us assume that acquisition is perfect and the “facts” we acquired are absolutely correct. There is still one issue: How accurate can people remember what they previously saw/heard? If they couldn’t remember well, or the memory is distorted or manipulated by themselves and outside forces, the “facts” they relied on afterwards would be wrong. It is hard to make good decisions using incorrect “facts”.

(1) Acquisition of “facts”

How do we acquire knowledge? People have been pondering this question since ancient time. In Greece, philosophers such as Plato and Socrates discussed it. For example, Plato (approximately 428-348 BCE) wrote at least two books on it (Meno and Theaetetus). Later philosophers continued to work on it. For example, Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) wrote three masterpieces related to the subject (Critique of Pure Reason, Critique of Practical Reason, and Critique of Judgment). In Asia, both Chinese and Indians had studied these topics. For example, in the pre-Qin period in China (before 200 BCE), there was a book called "Mo Zi" that discussed logic and knowledge in depth. In India, various philosophical/religious schools developed theories on it. We found the Asian approach more down-to-earth and is better suited for our discussion.

One of the ancient Indian schools within the “Hindu umbrella”, the Nyaya, was famous for investigating logic and epistemology (the theory of knowledge). Other Indian schools expanded on the investigation. We quote one short sentence from a treatise of the Yoga school, The Yoga Darśana, to help our understanding.

Section 1, sutra 7: “Perception, Inference, Testimony are the Right Notions” (From The Yoga Darśana as translated by Sir Ganganatha Jha).

The translator, Sir Jha (1872-1941) was a scholar of Indian philosophy and Buddhist philosophy. He provided commentary to the treatise. The following are excerpts of his commentary to the above short sentence:

Perception: “The internal organ being affected by the external object through the path-way of the sense-organs”. [Basically, this is the result of the interaction between our senses (eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, mind) and external objects. In the big fire example, the eyes of the residents see the flame, ears hear the sound of sirens, nose smell burned wood, and body feel the heat of the fire. In many Indian schools, the mind is considered one of the internal organs because our mind can evoke images, which sometimes go to memory as "facts."]

Inference: “Of the object of inference there is a certain relationship which is common to all homogeneous objects, and dissociated from the heterogeneous ones; the function, having this relation for its object, concern chiefly with the ascertainment of the generic (character of things), is Inference. As for example – The planets have motion, because they approach different regions, like Chaitra*; – the Vindhya Mountain having no such approach, has no motion.” (* Note: Chaitra is the first month in Hindu calendar). [Basically, inference is the application of logic and common sense to infer relationship between objects. For example, when we see that an object is at different regions at different times, we can infer that the object is moving. In the big fire example, some bystanders may not be in a location that allows them to see the flame, but they can infer that there is a fire from the smoke and the presence of fire-trucks.]

Testimony: “A certain object, having been either perceived or inferred by an authoritative person, is verbally expressed for the sake of transferring that cognition to another person.” [In the big fire example, the reporters provide testimony of the fire to the rest of the city residents.]

Each mode of acquiring “facts” has problems. Are our senses accurate? How good are our logic, common sense, and analytic ability? How reliable is "testimony"? These issues will be studied on this site. The “facts” we acquire may not be the real facts.

(2) “Facts” after acquisition

Many people believe that human memory is similar to a computer hard drive memory: we can record events in the hard drive and later recall these events with fair amount of accuracy. Unfortunately, our memory doesn’t work this way. According to Elizabeth Loftus, a cognitive psychologist and expert on human memory: “Memory works a little bit more like a Wikipedia page. You can go in there and change it, but so can other people.”

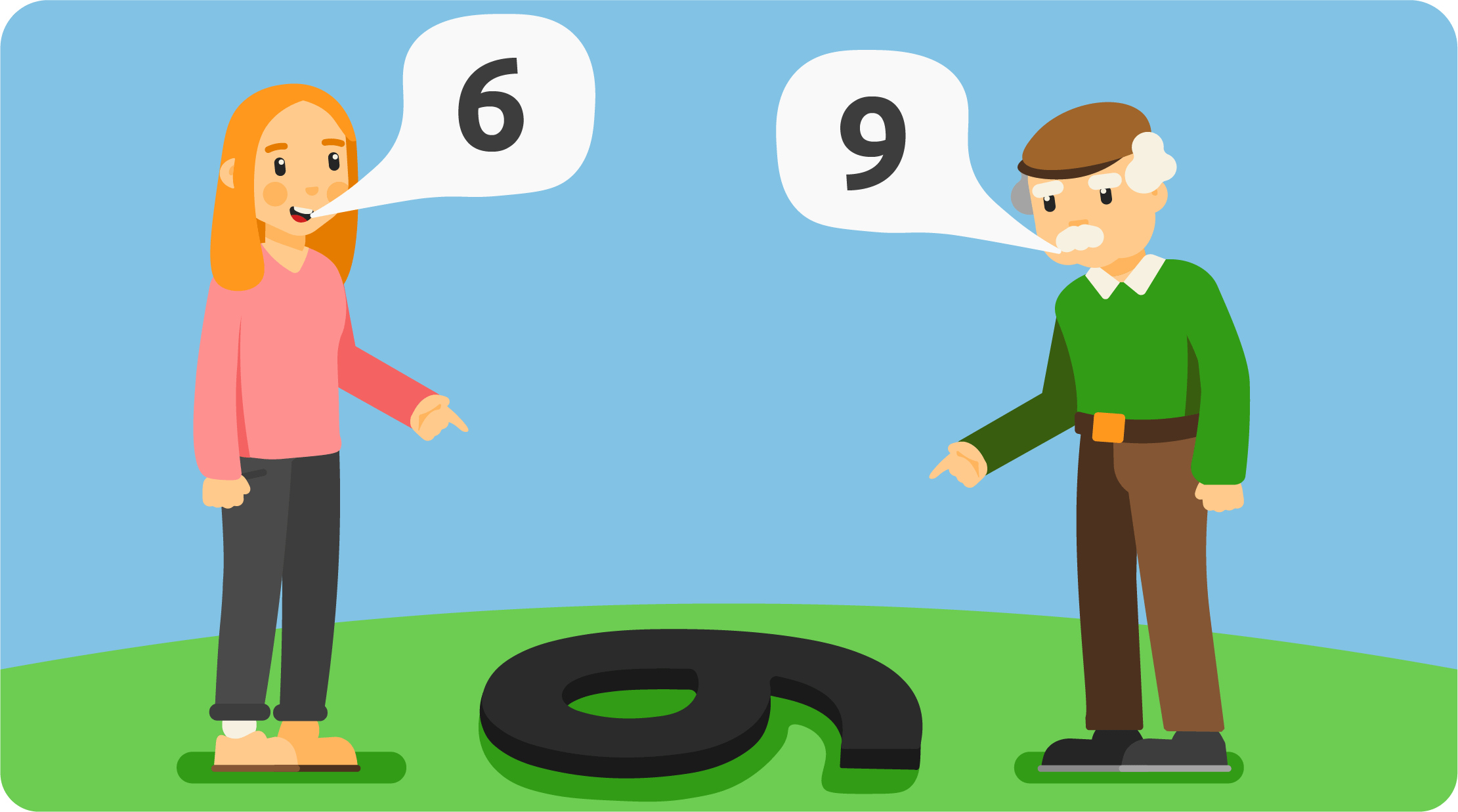

Basically, our brains can change our knowledge of “facts” even though we are unaware of the changes. The changes can be caused by ourselves and other people. This means that lots of “facts” we remember, assuming that they are correct at the time of acquisition, turn out to be distorted and even 100% opposite of the “facts” at acquisition.

The issues outlined above are complex. Some of them are not fully understood even today. A large number of people have been conducting research on various aspects of these issues. As far as we know, no one has developed a comprehensive theory of these issues and a good solution to the problems. Consequently, we will not (and cannot) present a “theory” and a “solution” to the issues. Instead, we will look at a large number of cases to gain insights and, hopefully, learn to improve our perception and retention of “facts.” Currently the site have n English pages of cases (most of the pages discuss one case while some of the pages discuss multiple cases), and a few essays (some of the essays also contain cases). Our sister website contains m Chinese pages of cases (some of the Chinese pages have English translation). All except a small number of the pages involve real persons and events. People and events are complex and multi-dimensional. These cases are best used for face-to-face discussions. By asking one another questions and offering feedbacks, we can deepen our understanding of the issues.

If you are interested in this topic, log-in at right to read the cases and essays on the site.